The losses accrue and reminders are daily this time of year. Barry N. Malzberg died a year ago yesterday. We lost Carl Sagan twenty-nine years ago today. Both writers had an outsized influence on me. One, as a mentor, and writer whose subject matter and style resonated with me as no other writer before. The other, as a scientist and writer whose clear, rational thinking deeply influenced my worldview.

I've been thinking about Barry a lot this last week, as I re-read his magnificent collection of essays, Breakfast in the Ruins, a book I first read in 2007, but even before that, I'd read his The Engines of the Night—which makes up the first half of Breakfast—a lifetime ago this month, December 1998. His essays on science fiction resonate more with me today than they did in my youth. I feel I understand and empathize with his central complaint of the genre more than I ever did before. I came to the genre as he did, and my trajectory, not nearly as meteoric, prolific, or bright, turned me off to the genre for a long time.

That arc was fueled first by a sense of wonder, and later by the realization that I had some ability to put a story together. As I read more about the people behind the stories, the arc was fueled by a desire to be like them, to join the ranks, as Jack Williamson put it to Asimov on a postcard. When I finally did join the ranks, the arc flattened. The achievement dulled the work. Conversations were no longer about the literature of s.f., they were about editors, word rates, SFWA business meetings, unacceptable contract clauses, the politics of science fiction, which was the politics of society writ large. No one, it seemed, wanted to talk about the stories; mechanics, yes, work methods, plotter or pantser, absolutely, but not about the work, not about how science fiction was or could be just as powerful as its literary counterpart. Not even I. From there, after I achieved the “cover” for the May 2015 issue of InterGalactic Medicine Show for my story “Gemma Barrows Comes to Cooperstown”, there was a rapid descent, the drogue shoot failed and while I survived reentry, I plummeted into he sea for reasons at the time I did not fully understand.

Re-reading Breakfast in the Ruins has helped to clarify this. I was trying, with my stories to write literary stories that had a science fiction background for convenience of market. With few exceptions, the tropes of science fiction were little more than window dressing to the character and their actions. “Gemma Barrows” was a baseball story, my send up to W. P. Kinsella. “Big Al Shepard Plays Baseball on the Moon” was an earlier attempt at this. “Flipping the Switch” was a literary story about the rapid passage of time, set in a science fiction background because I knew little else. “Take One for the Road” was a straight literary mystery wrapped in the cloak of science fiction (barely) and managed by the skin of its teeth to find its way into ANALOG. Barry's thesis throughout much of his critical writing about the genre was that we are capable of literary quality stories (there are many, many examples of this) that just happen to take on the cloak of science fiction and that should not diminish work. As I wrote my stories I had my college creative writing professor, Stephen Minot, forever in my head, asking me, “Why do you waste your talent on that genre junk?” Barry knew why. He had the reasons down cold.

Barry's knowledge of the genre was encyclopedic, but his knowledge of literature outside the genre seemed equally encyclopedic to me. He had the chops to make the comparisons. Re-reading Breakfast I wish, I desperately wish, he was still around so we could talk about the book, his ideas, his criticisms about the literature, as we did on a couple of occasions as we walked circles around the parking lot at Readercon. Barry was holding the genre to a higher standard and I think he improved the quality of the literature of the genre as whole with that standard. It is a standard that will never be met. It is an impossibly high standard, but in its impossibility lies that germ that improves the quality of the work, helps if grow stronger and stronger with each passing year. As he would say, he tried. But the conditions were impossible.

Barry's knowledge of the field led him to write some powerful pieces of criticism. His “Tripping with the Alchemist” is an absolutely stunning look at the field through he lens of a fee reader at the Scott Meredith Literary Agency. Each of his pieces on writers such as Alice Sheldon, Daniel Keyes, William Jenkins, and Isaac Asimov moved me to tears for different reasons. He reminded me of what great science fiction can be.

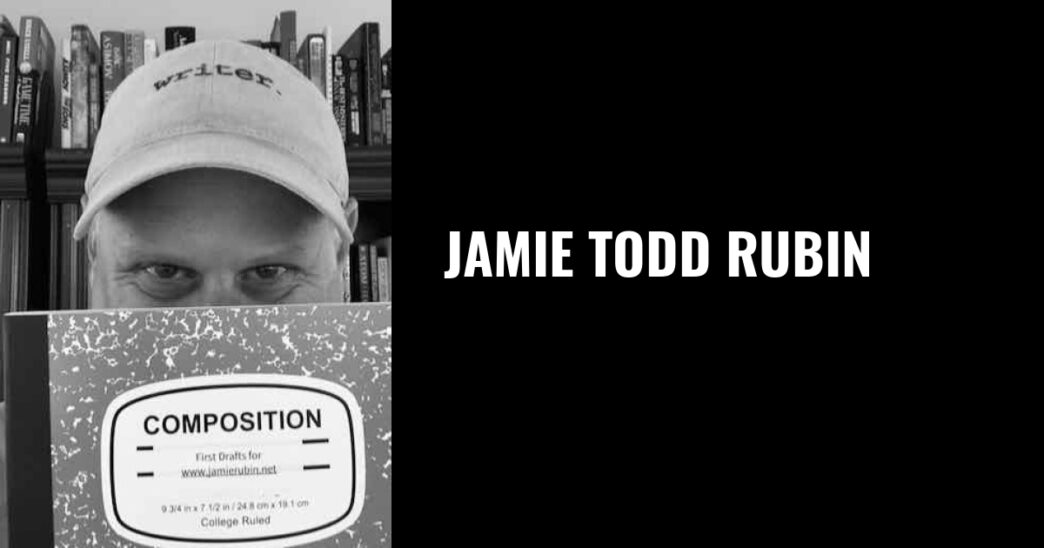

Normally, on our December sojourn to the warm climes of Florida, I take a break from my normal reading and spend a couple of weeks on “guilty pleasure” reading, pouring through Hollywood memoirs, especially older Hollywood. I'd had a list planned out for the trip this year: a re-read of Gary Giddins' 2-volume biography of Bing Crosby, Quentin Taratino's Cinema Speculations, Roger Ebert's Great Movies collections. Barry changed my mind. He reinvigorated in my the sense of wonder from a different perspective, a literary perspective, and I decided to revisit works that I'd read early on when I swallowed them whole without the experience of equipment to properly digest them. So my vacation will be spent re-reading Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land and Double Star, Bester's The Stars My Destination and The Demolished Man, Silverberg's Up the Line, Malzberg's Galaxies; as well as some of the best short fiction of the genre through the volumes of Silverberg and Bova's Science Fiction Hall of Fame. I come to these with a different mindset than the first time I approached them decades ago. I come to them now one who has, like Icarus, flown on wings of wax, too close to the sun, and who fell into the sea. But I didn't drown. Barry's book found me, on the anniversary of his passing, and from this lifeboat, he reached out his hand, pulled me to safety, and said, “Come on, kid, you can do better than that. I know you can.”