A reader says,

“Sorry/not sorry to have to call this out, but the example used of consideration of transmogrifying from an ER physician to an urgent care physician was being proposed in this article as the “cost of missed opportunity” with the shibboleth “Higher job satisfaction” attached to urgent care physician. Huh? Surely the author doesn't mean professional satisfaction, that Socratic self-examination process that gives you a sense of assurance that you've properly used as a good steward the unmerited DNA gifts & opportunities you were given to achieve the greatest good: Taking care of the ungodly sick, passing on to the next generation those pearls of wisdom you've picked up over decades, extending the frontiers of medical science. For many, it's either that or take the softer road of “higher income, better working conditions, respect from colleagues” while you avoid mirrors for the rest of your professional career. Differentiating from a pluripotent young professional into a narrower focus as you age is a natural phenomenon and is not a self-identity betrayal. After a 33-year career in academic medicine, I'm not seeing a bulwark of physicians eschew that process; I don't see them as dumb or stubborn. You don't have to commit to a wholesale substitution of your career choice to avoid burnout; you can continually improve yourself & refine your areas of expertise, something that feels natural and nearly effortless, without abandoning the entire panoply of your skillset. Some may not find my judgments & comments particularly palatable, but consider that this article was written by a hospitalist.”

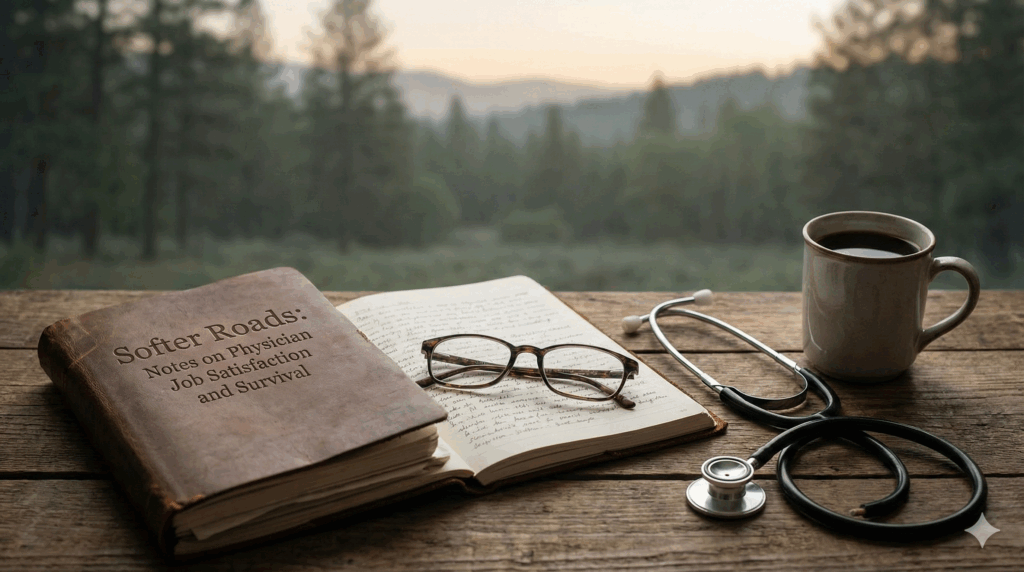

(This comment is from my piece, When Doctors Can't Let Go: The Sunk Cost Syndrome – Diagnosis, Treatment, Recovery. This post is in no way a callout or attack upon the comment's author. I love comments and appreciate everyone taking the time to share their perspectives. I thought about the one mentioned above for quite a while, because it hit home.)

I am a hospitalist. That shapes my viewpoint just as your 33-year academic medicine career shapes yours.

Your description of professional satisfaction that includes caring for the critically ill, teaching the next generation, advancing medical science, etc., deeply resonates with me.

But here's what strikes me as funny: we spend years learning to diagnose disease, but we're absolutely terrible at diagnosing our own career pathology.

A cardiologist wouldn't keep a patient on a failing medication regimen just because they'd already tried it for three years.

Yet when it comes to our own careers, we cling to bad treatment plans like they're gospel, call it dedication, commitment, professional excellence, when really it's just fear dressed up in a white coat.

The medical term is sunk cost fallacy, and it's killing us.

When Doctors Can't Let Go: The Sunk Cost Syndrome – Diagnosis, Treatment, Recovery

After years of training, medicine burrows into our identity so deeply it feels like chromosomal integration, like the DNA itself has been rewritten to code for stethoscopes and EMR passwords and the particular way we sign our names with those two letters that cost us everything.

We don't just practice medicine — we ARE medicine. Our residency program directors said so. Our parents told their friends. Our loans demand it, those monthly reminders arriving like clockwork, like rounds that never end.

But what happens when the DNA we thought defined us starts causing autoimmune destruction, when our own bodies turn against themselves, when the very thing that was supposed to save us starts killing us instead?

Burnout hit epidemic levels before COVID. Now? The disease has metastasized.

Some of us discover our desire to practice medicine — particularly direct patient care — has changed. Not temporarily. Definitively.

The Pathophysiology of Staying

Commitment and specialized knowledge keep medicine functioning, no argument there, but that same linear training — four years undergrad, four years medical school, three to seven years residency, maybe fellowship if you really wanted to delay life a bit longer — creates a cognitive straightjacket when we need flexibility, when the world outside our hospitals has shifted and pivoted and reinvented itself three times over while we were learning to intubate.

Medicine taught us protocols. Algorithms. Step-by-step approaches to complex problems.

Beautiful for treating sepsis, for running a code, for managing DKA at three in the morning when your brain is mush and you need the algorithm to think for you.

Terrible for navigating a non-linear world where career pivots happen constantly, reinvention is normal, and nobody blinks when someone leaves tech to start a bakery or quits law to become a photographer.

So we stay. Not because staying makes sense. Because leaving feels impossible.

I remember sitting in the physician's lounge at two AM during my third year of residency, watching an attending stare at nothing, just stare at the wall with this look I couldn't quite place then but recognize now as the face of someone who's already left but whose body hasn't gotten the message yet.

The sunk cost fallacy whispers during every night shift like that, whispers in your ear while you're trying to sleep during the day with blackout curtains that never quite block out the sun.

“We've invested too much money. Too much time. Too many years of delayed gratification. We can't quit now.”

Business schools teach this concept in week one. Physicians? We marinate in it for decades without recognizing the diagnosis.

Here's what the fallacy looks like in practice: An emergency physician works their fourth consecutive night shift, their marriage circles the drain, their kids ask if they still live at the house, they can't remember the last time they didn't feel hollowed out like someone scooped out everything that used to matter and left just the shell.

But they stay because they've “invested too much to quit now,” because the loans won't pay themselves, because what else would they do, because everyone's watching and everyone has opinions about what real physicians do and don't do.

That's not dedication. That's pathological adherence to a failed treatment plan.

Reframing the Investment

The word “sunk” carries baggage. It implies our training was wasted. Valueless. A ten-year mistake we can't recover from, ten years flushed down some cosmic drain while everyone else was buying houses and having babies and building normal lives.

Wrong.

Think of it differently. We didn't waste those years — we completed the most rigorous clinical training on the planet, learned to function on three hours of sleep and hospital cafeteria coffee, developed pattern recognition that transfers everywhere, even if we don't see it yet.

We learned to function under pressure that would break most humans, to synthesize complex information while someone's crashing in front of us, to communicate with diverse populations who are scared and angry and don't speak our language, to make life-or-death decisions with incomplete data because complete data is a luxury we never get.

Those skills aren't sunk. They're transferable capital.

But — and this matters more than anything — past investments can't dictate future decisions. The money we spent on medical school is gone, whether we practice for one year or forty, whether we become department chairs or quit to sell real estate, it's gone either way.

Those years of residency happened. We can't get them back by staying miserable, can't redeem them through suffering, can't make them worth it retroactively by destroying ourselves now.

The only question that matters: what makes sense moving forward?

An attending once told me he stayed in academic medicine for eight years past his burnout threshold because leaving felt like admitting failure, like standing up in front of everyone and announcing he'd been wrong all along, that he'd wasted his time, that he couldn't hack it.

Eight years.

When I asked what changed, he said, “I realized I was already failing. Just failing slowly, like a patient bleeding internally, losing just enough blood each day that nobody notices until one day you code on the table and everyone acts surprised.”

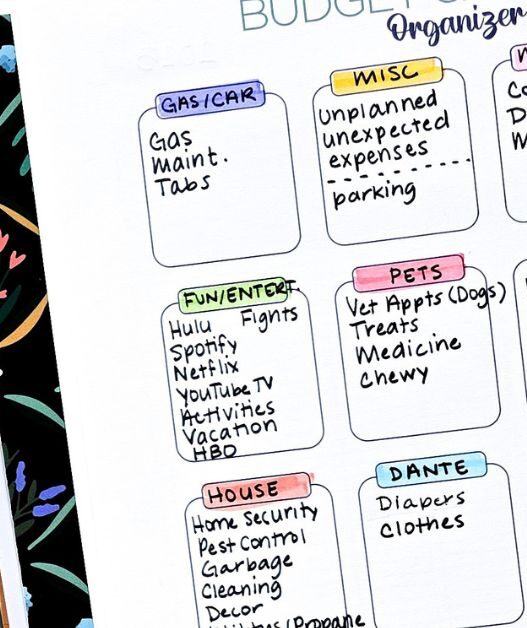

Vital Signs of Career Crisis

Some questions function like diagnostic tests, reveal pathology we've been ignoring the same way we ignore our own chest pain, or that persistent cough or the fact that we haven't had a physical in six years, because physicians make terrible patients.

What opportunities are we missing by staying trapped in sunk costs?

The urgent care job that would let us see our daughter's soccer games instead of just hearing about them later, the consulting work that uses our medical expertise without the moral injury of boarding psychiatric patients for 72 hours in hallway beds, the locums gigs that would let us travel between assignments, see the world, remember what it feels like to wake up somewhere and not immediately feel dread?

What new information might have influenced our original choice?

We picked emergency medicine at 24 because we loved the adrenaline, loved the chaos, loved feeling like we mattered in those moments when everything hung in the balance.

We're 42 now with untreated depression and PTSD from violent patient encounters, from being spit on and punched and threatened, from watching people die who shouldn't have died, from the accumulated weight of a thousand small traumas that nobody talks about because we're supposed to be tough.

Did you know that emergency physicians have among the highest suicide rates in medicine? So, I don't think it's about taking “softer roads” or avoiding mirrors.

It's clearly about physicians dying because they stayed in careers that were killing them in every way possible: physically, mentally, and emotionally.

That's new data. It matters.

Are we equating change with quitting?

This one destroys physicians more than anything else, this inability to see the difference between strategic retreat and cowardice. We conflate career transition with professional failure, with weakness, with not being good enough or strong enough or dedicated enough.

But what if change is actually the courageous decision, what if recognizing that emergency medicine is destroying us and choosing something else demonstrates wisdom rather than weakness, what if the real failure is staying in a job that's killing us because we're too proud or too scared to admit we need out?

The emergency physician transitioning to urgent care isn't betraying their calling. They're answering a different one: stay alive.

The Cost of Being Right

We chose emergency medicine for good reasons back then, reasons that made perfect sense at the time. The intellectual challenge. The variety. The impact.

The feeling that we were doing something that mattered, that every shift could be the shift where we saved someone's life. We weren't wrong then.

But “being right” about our past decision doesn't obligate us to future suffering, doesn't mean we have to honor that choice forever like some kind of blood oath we swore in the dead of night.

Markets change. Companies pivot. Entire industries reinvent themselves. I would've laughed in the face of anyone who claimed Artificial Intelligence could hurt physician careers. Yet, I see at least one such article claiming AI will replace physician jobs almost every other week now.

Why do physicians insist on lifetime commitment to choices made before our frontal lobes fully developed, before we knew what shift work really meant, before we understood that the reality of medicine bears almost no resemblance to the version they sold us in medical school?

I see this constantly in the hospital hallways and physician lounges and at conferences where everyone's three drinks deep and finally honest.

Physicians torture themselves maintaining positions that align with external definitions of excellence while destroying their mental health, grinding themselves down day after day, shift after shift, until there's nothing left but obligation and resentment and the faint memory of why they wanted this in the first place.

They're right about their specialty's value. They're right about their clinical skills. They're right that academic medicine advances science and trains future physicians and serves a noble purpose that matters deeply.

They're also suicidal.

Being right doesn't keep us alive.

Pattern Recognition From Previous Pivots

We've already done this, made hard choices and walked away from things we'd invested in. Maybe not with careers, but we've abandoned sunk costs before and lived to tell about it.

Remember switching from that research project that wasn't working, the one we'd spent six months on before finally admitting it was going nowhere?

Changing residency programs after that first year when we realized we'd made a terrible mistake? Ending that relationship that consumed three years but wasn't viable, walking away even though everyone said we should work harder at it, try couples therapy, give it more time?

We let go. We moved forward. The world didn't end, the sun kept rising, we survived and maybe even thrived once we stopped trying to force something that wasn't working.

Career change is the same process, just higher stakes, just more money involved, just more people watching and judging and offering unsolicited opinions about what we should do with our one wild and precious life.

What would we tell another physician in our situation? Seriously, think about it. Our co-resident confides they're miserable, fantasizing about leaving medicine, drowning in regret and student loans, and the growing realization that they've made a catastrophic error.

Would we tell them to tough it out? Honor their sunk costs? Stay in a career that's killing them because other people have expectations?

Of course not. We'd tell them their mental health matters.

Their family matters. Their life matters more than theoretical professional obligations, more than what their program director thinks, more than preserving some abstract notion of what it means to be a real physician.

So why doesn't that advice apply to us?

The Peanut Gallery Problem

Are we making our own decisions or listening to a very noisy crowd that never shuts up, never stops having opinions, never stops judging every choice we make?

Our program directors have opinions about career trajectories and what constitutes success.

Our parents have expectations they've held since we were twelve and announced we wanted to be doctors. Our colleagues have judgments about who's tough enough and who's taking the easy way out.

Social media has hot takes from people who don't know us and never will. Everyone knows what “real physicians” do, what choices are respectable, what paths demonstrate true commitment versus just going through the motions.

But — and I cannot stress this enough — none of them live our lives, none of them wake up in our bodies feeling what we feel, none of them will be there when it all falls apart.

Emergency physicians have among the highest suicide rates in medicine, higher than almost any other specialty, a fact that should shame us all.

When our attending lectures about professional excellence while we're planning our own death, while we're driving home after a night shift and thinking about how easy it would be to just drift into oncoming traffic, their opinion becomes irrelevant, becomes background noise, becomes just another voice in the chorus that doesn't matter when survival is on the line.

The peanut gallery won't show up at our funeral. They won't raise our kids. They won't support our spouse.

They'll just move on to the next physician who “took the soft road” and gossip about them instead, shake their heads sadly over coffee, and wonder aloud what happened to professional standards these days.

Calculating the New Equation

What's our cost/benefit ratio now, today, this moment, not in theory but in reality?

Not theoretically. Right now. This month. Today.

The emergency department pays $280,000 but costs our marriage, our sleep, our mental health, any relationship with our children who barely know us anymore and will soon stop asking when we're coming home.

Urgent care pays $180,000 but gives us weekends and predictable hours and the mental space to remember why we liked medicine in the first place, before it became this grinding obligation that consumes everything good in our lives.

Do that math honestly, without flinching, without the rationalizations we're so good at making.

I'm not suggesting everyone should leave their specialty, pack up and walk out tomorrow without looking back.

Some physicians genuinely thrive in high-acuity environments, love the chaos and the adrenaline and the feeling of making split-second decisions that matter.

If that's us, fantastic. Stay. Excel. Teach others. Become the best version of that physician you can be.

But if we're staying because of sunk costs while our mental health deteriorates, while our relationships crumble, while we're counting down the hours until we can escape for another brief period before returning to the job that's destroying us piece by piece? We're mistaking stubbornness for nobility.

Survival as Success

The emergency physician who transitions to urgent care after recognizing burnout has succeeded at the most basic level: survival, the fundamental requirement for everything else that matters in life.

That's not professional failure. That's clinical competence applied to our own case, the same diagnostic skills we'd use on any patient who walked through our doors.

We wouldn't keep a patient on chemotherapy that was killing them faster than their cancer, wouldn't watch them waste away and call it treatment, wouldn't insist they honor their commitment to the protocol even as it destroyed them.

We'd change the regimen. Adjust the approach. Try something different, anything different, because the goal is survival and everything else is secondary to that.

Why is our career different?

Medicine embeds itself deep, I know, deeper than anything else in our lives except maybe our children's faces and the sound of our own heartbeat in quiet moments.

After all those years, it feels like abandoning medicine means abandoning ourselves, like cutting away part of our identity and becoming someone unrecognizable.

But choosing a different path within or adjacent to medicine isn't betrayal, isn't weakness, isn't failure by any reasonable standard.

It's adaptation.

The softest road leads to a physician's funeral, to colleagues standing around awkwardly, wondering if they should have said something, if they saw the signs, if they could have done something differently. Any other path — urgent care, telemedicine, consulting, administration, medical writing, anything that lets us use our training without destroying ourselves — beats that outcome.

Our training wasn't wasted. Our years weren't for nothing. But they're already gone, spent, finished, complete. They can't be recovered by staying miserable, can't be redeemed through suffering, can't be made worthwhile retroactively by sacrificing our future to honor our past.

The only question left: what do we do now?

![How to Watch MeTV Without Cable [Stream MeTV Live]](https://rjema.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/How-to-Watch-MeTV-Without-Cable-Stream-MeTV-Live-527x630.jpg)

![How to Get Free Cable TV [Free TV Legally]](https://rjema.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/How-to-Get-Free-Cable-TV-Free-TV-Legally-527x630.jpg)