Note: I'm cleaning up the blog for its 20th anniversary. This episode of my Vacation in the Golden Age only appeared on Medium, at a time when I was experimenting with that platform. I am moving here where it belongs.

I wrote Episode 40 of this Vacation in the Golden Age in October 2012. Four years later, I'm back on Vacation, with Episode 41. Four years is a long hiatus, and a lot has happened in that time, but I've wanted to get back to this Vacation and do my best to see it through, and this new installment is the beginning of that effort.

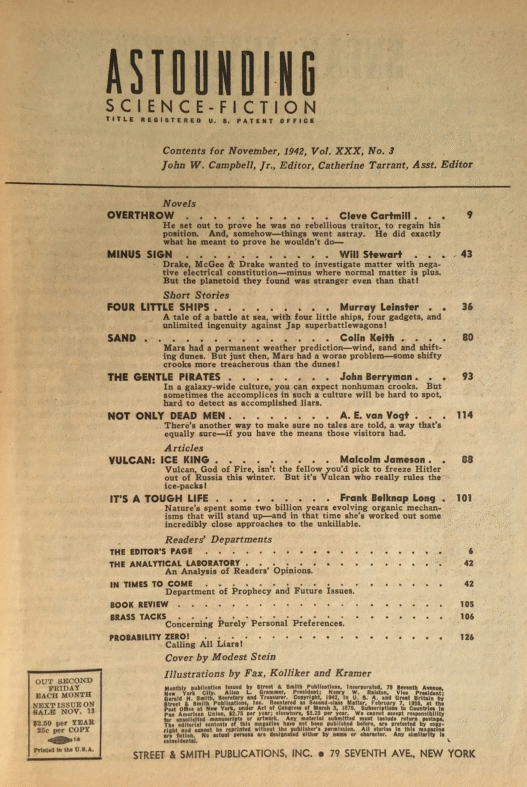

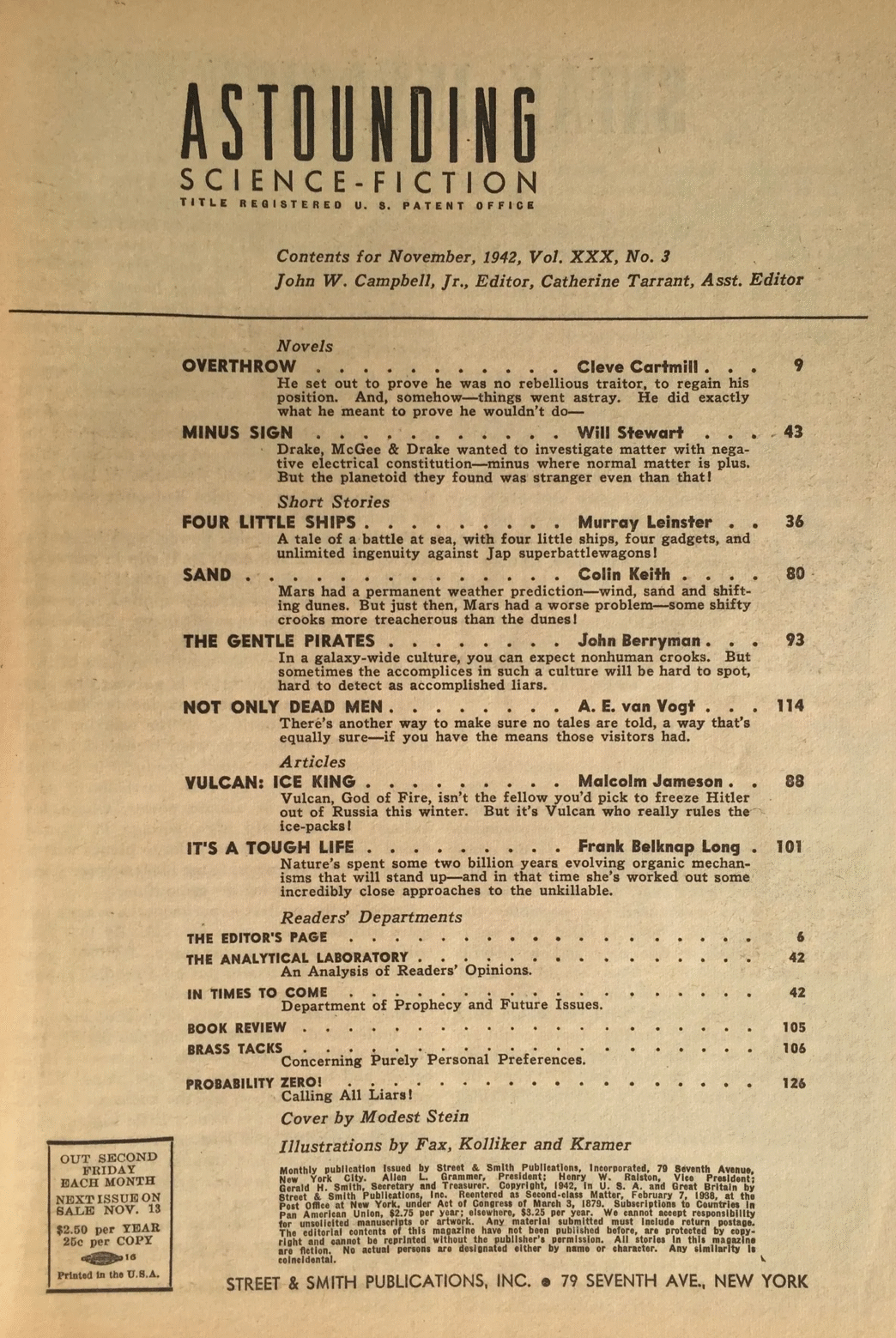

We left off in the fall of 1942, with the United States involvement in the Second World War nearly a year old. John W. Campbell, editor of Astounding had been complaining about all of the writers and artists he'd been losing to the war effort: Heinlein (and Heinlein's pseudonymous Anson MacDonald), A. E. van Vogt, Huber Rogers, and many others. And yet, the stories in Astounding continued to flow from writers, both in and out of the war.

The cover for the November 1942 issue, by Modest Stein, depicts an early scene from Cleve Cartmill's lead story in the issue, “Overthrow.” I wasn't impressed by the cover, having been spoiled by countless beautiful Rogers covers. Campbell bills “Overthrow” as a novel. Indeed, two novels appear in this issue, as well as 4 short stories, and two science articles.

Editorial: “Sneak Invasion”

Campbell's editorial this month centers around how new technologies tend to sneak into our daily lives, almost unnoticed. At the time I first read this editorial, Trevor Quachri, current editor of Analog asked me if I'd write a guest editorial for the magazine on a short deadline. This would be my second guest editorial for Analog (my first, “Gem Hunting” appeared in the June 2013 issue), and I was flattered that Trevor felt I could deliver on short notice. I took up Campbell's editorial and wrote a response to it, which I called, “Sneak Invasion, Revisited.” You can find it in the March 2015 issue of Analog.

In his editorial, Campbell writes,

The new techniques filter into normal life so smoothly, in such small steps, with so much forewarning, that they never surprise us. No company manufactures new devices until they've prepared the public to receive them and use them.

In my response, I wondered how a science fiction writer from 1942 might respond, if pulled through a time into 2015, perhaps by a lightning bolt, a la L. Sprague de Camp's Lest Darkness Fall. Would our present be a recognizable future to that science fiction writer? Campbell was largely right in this case: when you live through the changes, you are well-prepared for them, and they sneak in. But if you skipped over those incremental changes, how different would things seem? And, of course, how will these sneak invasions alter our own future, what will the world look like, say 70 years from now, and will our kids even notice the changes?

“Overthrow” by Cleve Cartmill

Blurb: His idea was to prove he'd been falsely accused, to prove he was an honest, sincere upholder of the government. Somewhere, things got confused — and he did what he set to to prove he wasn't doing!

“Overthrow” is the first of two complete novels that appear in this issue of Astounding. So far as I can tell, it is the first time that two novels have appeared in a single issue in the course of my Vacation. We've seen one other complete-in-an-issue novel, and that was Robert Heinlein's “Waldo” (August 1942, Episode 38)

Cartmill's latest is a fairly typical class-struggle story that we've seen before in this vacation (like de Camp's “The Stolen Dormouse” for instance). Cartmill's writes in classical Golden Age style, with lots of adjectives thrown in for good measure:

Captain Jorgeson fixed the screen with a bright-blue glance. His great hands knotted. His face flamed as red as his hair.

What makes the story a little less typical is that the struggle takes place through the efforts of Josh Cameron to demonstrate that he has been falsely accused of rebelling against the current order. In order to prove his innocence, however, he is forced to rebel.

Cartmill does a pretty good job of describing a future society, without being overly preachy about its structure, the way Heinlein can sometimes be, but the vision of that future society is fairly immature, with segments of society coalescing into “centers” of various industries, none of which seem to entirely trust the other, but completely dependent on one another for survival.

And then there are the outlaws, the people living outside these social structures. Robert Silverberg would do this far more successfully in his novel The World Inside, decades later.

Ultimately, I thought the story was overlong for its topic. There were interesting subplots, like the “contraterrene screen” that the outlaws used to help balance the power against the centers. This was a kind of early nuclear detente before the advent of atomic weapons. But really, the story could be summarized by a single line of dialog that takes place when the outlaws are trying to convince Cameron of their position. Cameron cannot seem to get it through his head that the centers are anything but the one true way of life, and that all the outlaws are looking for is a ways back in. They counter with a simple question:

Has it ever occurred to you that they may not want to go back?

This, coupled with the way that Cameron is forced to rebel in order to prove his innocence, redeem an otherwise overly long story on social structure.

“Four Little Ships” by Murray Leinster

Blurb: An old favorite of science-fiction is back again with an ingenious tale of little ships and special gadgets — ordinary sorts of gadgets — and a naval victory that didn't need battleships or planes or air carriers. Just — ingenuity and planning, plus four little ships.

Part of the delight of this Vacation is discovering hidden gems. I wrote about this in a guest editorial title “Gem Hunting” in the June 2013 Analog. There are gems that are well-known, among them, in my opinion, L. Ron Hubbard's “Final Blackout.” But it is the lesser-known gems that I discover along the way that make this Vacation a pure joy. “Rust” by Joseph E. Kelleam is one example. And, much to my surprise, “Four Little Ships” by Murray Leinster (a.k.a. Will Jenkins) is another.

The story is unlike anything I've read in Astounding. Like many of the gems I've encountered, it is barely even science fiction. Instead, it is the story of four minesweepers during a war. Or, as the story opens:

This is the story of four little ships in wartime.

The story itself reads like something you might find in James Michener's Tales of the South Pacific, where the ships are the characters in the story. The little mine sweepers, coming out ahead of battle to clear the waters for their big brothers. The Heron, Tanager, Gannet, and Thruh work the seas as battles rage.

Leinster's writing is anything but purplish in this piece, and despite the story being completely narrative, it carried me away with its description, for instance,

Down below the horizon, momentary flashes looked somewhat like pale heat lightning. But it was air bombs — heavy ones. The mine sweepers paid no attention. They were busy. From time to time the heavy, booming sound of a detonating mine arose form the Challoner Bank. Then buzzing began overhead. A flare blossomed in the sky. The mine sweepers plowed on their way. The buzzing grew louder and became roars. Streaks of colored sparks darted up from one mine-sweeper and then from another. Sharp, cracking detonations told of bombs dropped upon them as targets. They went on, firing their machine guns with complete futility.

The passage reminds me of Hemingway, and the tone carries through the entire short story. Days pass in paragraphs, Monday to Tuesday to Wednesday, and on, but the descriptions of what the four little ships see on their missions carry us on, beauty amid destruction:

The palms on the island let their fronds droop discouragedly. The surf boomed languidly on the beaches. The only activity anywhere was the planes, which buzzed continually above the island. Now and again one of them darted away toward Mahapa, and now and again another came back. But there was no gunfire of any sort. The enemy did not appear to attack Kaua. Nobody knew why.

Of course, it was the work of the four little ships. With their simple tools, they were out detecting and clearing mines, flummoxing enemy shipping, and while the technology was not described in any detail, it is what made the story science fiction — barely.

According to Murray Leinster: The Life and Works by Billee J. Stallings and Jo-an J. Evans, Leinster's mystery technology in “Four Little Ships” may have hit a little close to home:

The military censors were also interested in the Leinster story “Four Little Ships” when it was published in Astounding Science-Fiction (November 1942). This story described a way of disrupting enemy shipping using underwater sound transmission, which was, coincidentally, under military development at the time.

I read “Four Little Ships” twice — it is short enough. And while the Kramer illustration for it is appallingly bad, it is definitely my favorite story of the issue.

“Minus Sign” by Will Stuart

Jack Williamson, in his Will Stewart guise, is back with another Seetee story, this one a novel-length space opera dealing with the strange effects of contraterrene matter — or what we today would call antimatter. The story continues the saga that began in “Collision Orbit” (July 1942, Episode 37) Compared to the writing in “Four Little Ships,” the story felt unusually pulpy for Williamson. I lost count of the number of ways in the first few pages he referred to the hero of the story, Rick Drake, as tanned. They included, “space-bronzed” (multiple times within a few sentences), “his tanned, powerful fingers.” Suffice it to say, we get it. He was tan!

That said, the story moved quickly, and was a fun read. Drake wants to go back to mining with his father, and solve the mystery of what appears to be a Seetee asteroid that blows up. Captain Anders tries to oppose him in this, and for a while, things get confused. Working with his father's friend, Rob McGee, they race Anders to the asteroid to try and understand cryptic messages that have been received.

Ultimately, we discover that Seetee affects time in a strange way, and Drake and McGee actually travel back in time to make their claim on the Seetee rock.

There were interesting elements within the story. Williamson made valiant attempts at realistic science — setting aside the Seetee time-travel business. For instance in describing a space cruiser, he writes,

Two long spacial rifles, counterpoised in two opposite turret blisters so their recoils wouldn't spin the ship, lay flat and ugly against the hull.

My main problem wasn't the fault of Williamson at all. This was the second of two short novels in the issue. Not novelette, but novels, as listed in the table of contents. I think that was too much for a single issue of Astounding.

“Sand” by Colin Smith

Blurb: Mars is a desert world, a dry, rusted corpse of a planet. And deserts are always tricky things — but a world of shifting sand made trickier yet by shifty crooks —

Malcolm Jameson — in his Colin Keith disguise — provides us with a straight mystery set on Mars. “Sand” is the story of Special Investigator Billy Neville of the Interplanetary Police, and his attempt to help Martian authorities solve a series of diamond robberies taking place in the sand mines of Mars, and leaving behind a high body count.

The mystery itself is straight-forward, and perhaps even a little amateurish. It is framed as a locked-room mystery, with robberies taking place with no obvious way for the robbers to get into the mines, given how the mines are built, how the sands of Mars constantly shift, and the raging winds of Mars offering protection to the mines against unauthorized intrusion. As the local official explains,

What has us stumped is that all the robberies take place while the mine is submerged and yet no one ever enters through the trunk or leaves by it. How they get in and get away is what we want to find out.

Neville ultimately traces the villains to the company that constructed the mines themselves, creating a literal backdoor into the mine, one that faces into the wind, so that it would not be picked up during inspection. As I said, not a particularly strong mystery.

But I liked “Sand” because of the writing. This was not the typical pulpish story we still find in many of the Golden Age tales. The writing shows a maturity that Jameson has worked hard to gain over the years. It is different in tone from his “Bullard” stories, and he has clear control of what he is trying to do. The opening of the story illustrates this tone and control:

The grimmest joke on Mars is the daily weather forecast. You see it — if you can see anything — just as you leave the sky port at Ghengiz. It is engraved in inch-deep letters on a monolithic bloc of permalite, and even that unabradable stone is worn round on the corners from years of sand blasting. The standing prophecy says:

WEATHER FOR TODAY AND TOMORROW: Hot, dry, and windy, with sandstorms and shifting dunes.

It is a triumph of paradoxes, for it is not only a masterpiece of accuracy, but of understatement as well.

Jameson maintains this control throughout the story, and it makes for an interesting read, even if the mystery isn't a strong one.

Article: “Ice King” by Malcolm Jameson

Blurb: Vulcan, God of Fire and volcanoes, isn't the sort of being you'd ordinarily associate with the world's worst — and coldest — weather. But he's responsible — as Jameson shows.

We get a one-two punch of Jameson this Episode, first with his pseudonymous story “Sand,” and now with an article — his second in my Vacation. The article is on the subject of global climate, although it might not have been called such in 1942. In it Jameson takes us through the history of volcanic eruptions in human history, and how those eruptions seem to affect the weather in years afterward. It is a good article, and there are three things of particular interest.

First, the opening paragraph is one of those times in my Vacation where my knowledge of the future — or more aptly, the writers assessment of his present, diverge into different paths. Jameson writes,

It would be the height of irony if this coming winter Japan should annihilate Hitler and Nazidom. If it is done — and it may very well be — it will be done without intention or malice; even unwittingly. For by Japan is meant Japan, not its rulers, its armed might, or its people, but the island of Honshu itself — an inanimate thing of rock and soil.

Jameson goes on to point out that Asamayama has reported to have erupted, and if history is any judge, it could mean a cold winter for Europe — and more hardship for the German army. The rest of the article explains why this is so, but I find it most interesting that those winters didn't pan out quite the way Jameson hoped in 1942.

Second, Jameson quotes a remarkably prescient observation of none other than Benjamin Franklin:

During several of the summers months of the year 1783, when the effects of the Sun's rays to heat the Earth in these Northern regions should have been greatest, there existed a constant fog over all Europe and great part of North America.

Franklin lists the results of such “fog” on the climate and then goes on to postulate causes:

The cause of this universal fog is not yet ascertained. Whether it was adventitious to this Earth, and merely a smoke ball preceding from the consumption by fire of one of those great burning balls or globes which we happen to meet with in our course around the sun, and which are sometime seem to kindle and be destroyed in our atmosphere, and whose smoke might be attracted and retained by our Earth; or whether it was the vast quantity of smoke, long continuing to issue during the summer from Hecla, Iceland, and that other volcano which arose out of the sea near that island, which smoke might be spread by various winds over the northern part of the world, is yet uncertain.

Finally, Jameson, in providing the ultimate answer to the cause of the cold winter that follow volcanic eruptions — that of the volume of ash absorbing or reflecting sunlight — draws a distinction over which there is often still confusion today: weather vs. climate.

I enjoyed Jameson's article, and I found it mildly ironic that both his short story in the issue, and his science article essential dealt in dust.

“The Genetic Pirates” by John Berryman

Blurb: A neat little yarn that proves the old saying “Figures don't lie but liars figure” doesn't always have to apply to human beings.

John Berryman has an amusing story this month about space pirates. A passenger vessel moving between Leo III and Leo IX is hailed by pirates seeking out some diplomatic documents. So long as instructions are followed, no one gets hurt. This isn't the first time pirates have attacked ships on this run, however, and it piques the curiosity of one of the passengers, an alien named “Cash” Bowen, who happens to be a “detector calculator.” In other words, he designed the ships computers.

In a clever twist, it turns out that there really isn't another ship. As Cash intimates during the course of the story,

No, the very idea of spaceships contacting with each other while riding the geodesics smells bad mathematically.

Instead, one of the pilots, and one of the passengers are the pirates. Through manipulations, they make it seem as if there is a ship out there, and collect the diplomatic pouch without incident — until Cash catches on.

The story is told in first person, and Cash Bowen had an interesting interior voice. It was clear from early-on that the story was meant to be humorous. The clever puzzle and the humor in the story combined to make it a fun read.

Article: “It's a Tough Life” by Frank Belknap Long

Blurb: But some of the forms of live have developed toughness — and camouflage — to match. Frogs you can walk on without killing ‘em —

This months science article is not by Willy Ley or R. S. Richardson, but by Frank Belknap Long — the fiction writer, and horror writer. We've seen him once before in this Vacation, back in Episode 25, with his story, “Brown” (July 1941). But now, he's got a science article, a humorous one, and one that in addition is a direct response to a 2-part science article we've seen before. As long writes,

For two years now I have been brooding over Sprague de Camp's article, which was labeled: “There Ain't No Such.” Buttressed by an erudition surpassing anything I can hope to muster, De Camp made the wild life of Mars, Venus, and the great outer planets seem utterly prosaic by dishing up a few choice tidbits of sober natural history.

Long's “complaint” is that de Camp's article (November — December 1939, Episodes 5 and 6) makes it hard for science fiction writers to come up with unique aliens, because de Camp has shown just how diverse the animals on Earth really are. As he puts it,

Being a top-flight science-fiction writer himself, De Camp should have known better than to deprive his fellow scriveners of their bread and beer.

Not to be outdone, however, Brown has some of his own earth-bound creatures to add to the list. Arguing that the key factor is survival, he outlines several creatures, from the common freshwater eel (“five minutes in boiling water, and he's still thinking about raising a family) to a frog, Trichobatrachus robust, that can flatten itself out at the bottom of bonds.

It is a fun article, made more fun by the tone Long takes, and by the clear pleasure he has in the friendly mocking of de Camp, who I can only assume, was a friend in turn, and took it in the spirit it was intended.

Book Reviews: Shells and Shooting by Willy Ley by Robert Heinlein

Robert Heinlein makes a brief appearance this issue, one not listed in the table of contents, to review a book on ordinance by Willy Ley. The book is entitled Shells and Shooting, and Heinlein gives it high praise, saying,

Mr. Ley probably knows as much about the history and development gunnery as any man alive, and his treatment of modern weapons is authoritative and meticulously accurate.

While I can't speak to the book itself, not having read it, I have read several of Ley's articles on weapons in this Vacation (“Space War”, Episode 2, “The Magic Bullet”, Episode 10, “Bombing is a Fine Art”, Episode 38, and “The Paris Gun”, Episode 40) and I have enjoyed them all. Moreover, I have learned more from them about weapons than from any other nonfiction on the subject that I have encountered.

“Not Only Dead Men” by A. E. van Vogt

Blurb: There are times when silence is so utterly vital that lives mean little, times when the fact men are being silent, even, must not be known. For such cases, there are ways which lead to silence other than death.

“Not Only Dead Men” puts an interesting spin on a typical van Vogt “beast” story. The story involves a whaling ship in the Bering Straight that discovers what it thinks is a submarine, but what turns out to be an alien spacecraft. A lizard-like creature sets out to sabotage the whaling ship, and the crew fights back.

Eventually, they learn of the way the alien ship got to Earth, and of the other creature, very whale-like indeed, that it was fighting when it crashed here. The whalers attempt to fight the creature, and in their victory, seal their doom. As Dorno, the alien lizard explains,

When important assistance has been rendered a Galactic citizen or official, no matter what the circumstances, it is morally necessary to the continuity of civilized conduct that other means be taken to prevent the tale from spreading —

Dead men tell no tales. But… not only dead men. This is why the crew of the whaler have been stolen away.

It wasn't my favorite van Vogt by far, but Alva Rogers approved of it. In his Requiem for Astounding he wrote,

“Not Only Dead Men” by van Vogt, told of an American whaleship's unexpected involvement in an interstellar war, how the Americans helped one side, and how they were subsequently rewarded. A very nice switch, by van Vogt, on his monster theme.

Probability Zero: Calling All Liars

I have a suspicion that, at this point, the Probability Zero pieces Campbell is publishing are not exactly the type he had in mind. They seem almost as if they are jokes, always with some punchline at the end. Flash fiction today has improved upon the style (although the ending still sometimes leave something to be desired).

Avenue of Escape by Hal Clement

Some soldiers wonder how their esteemed mess sergeant managed to escape from almost certain doom when he was trapped in his fox hole. His avenue of escape turned out to be based on an arithmetic gimmick involving the number of gunshots per minute, and the muzzle velocity of the bullets. Absolutely improbably, and yet perfectly logical. This one is probably the closest of the batch to what Campbell intended.

Eureka! by Malcolm Jameson

Perhaps the most important thing about Malcolm Jameson's paradoxical “Eureka!” is that it marks his third appearance in this issue. I think that is a first for my Vacation. The story itself is about a universal solvent. It will dissolve anything. Including glass. Which makes one wonder about the container that holds it.

The Sleep That Slaughtered by Harry Warner, Jr.

Harry Warner, Jr.'s is a bit longer, and involves a man who discovers that he can do anything faster in his sleep. This is based on the premise that we can have what seems like a long dream in mere fractions of a second. So he learns to sleep with his eyes open and with the newspaper in front of him so that he can read the front page while he sleeps. He moves on to routine tasks, and ultimately enters an elevator to take him down one floor. The problem is that the elevator is air-tight and in his accelerated dream-state, he suffocates and dies.

The Green Sphere by Dennis Tucker

“The Green Sphere” in the story is over a mile in diameter and deadly after three days. To get if off the planet, they essentially build a massive pool cue through the earth and knock it off.

A Matter of Eclipses by P. Schyler Miller

Miller, who has been absent from the Vacation since April 1941, has a yarn in which Old Man Mulligan spins tall tales about times in which eclipses taking place on various planets (Mars, Jupiter, etc.) have saved his bacon and gotten him out of various scrapes.

Brass Tacks

In the first letter this month, James W. Thomas of Valley Falls, Rhode Island asks,

What is happening to Brass Tacks? If it deteriorates any more it will hit the low that did only once before in the history of the magazine. Does everyone agree with everyone else? Does no one feel in an argumentative mood?

He complains about the short shift the letters column has taken over the last several month. Campbell replies,

I guess too many readers are too busy making hardware for Hitler to write arguments to Astounding.

Still, after months of short letter columns, with just a handful of letters, we finally get our due. The Brass Tacks in the November issue is 8 pages of letter. That's 14 columns and 10 letters (some long, and some short).

Harry Warner, Jr. has a letter in this issue in which he makes the following observation about Heinlein and MacDonald's absence due to the war effort:

I believe I'll miss MacDonald more than Heinlein: the former's rambling plots had a freshness and novelty not to be found in Heinlein's work. And I can't think why.

Oh, the irony!

In an earlier Brass Tacks column, reader Earl C. Smith complained about excessive amounts of scientific explanations in stories. Campbell makes the following interesting observation in response to a Mr. Leonard Powsner who brings up a similar point:

If the author handles his material skillfully, he goes not need to take time out to explain his science — a practice Mr. Earl Smith objects to. It can be worked into the story without interruptions, as the top authors do. It takes immensely more skill, however.

I think Heinlein does a pretty good job of this, and it is what I try to do in my own stories. In my first Analog story, “Take One for the Road” (June 2011), I had one brief paragraph of “hard science” and it was to the best of my ability, built into the narrative of the story so as not to seem intrusive. I can't say whether or not I was successful, as I'm a terrible judge of my own writing — but I tried, and Stan Schmidt did publish the story.

Another reader from Great Britain complains that there are too many war-related stories. And Campbell asks for comments back from his readers? More war stories? Or none?

I have the same thought each time I dive into the Brass Tacks: who were the people writing these letters? Some of them — like Harry Warner, and Cleve Cartmill, who also had a brief letter in the issue — were well-known fans and writers. Others were just fans who took the time to write in, in one instance, from South Africa. I'd be hard-pressed to imagine any are still alive today, and some almost certainly died in the War. But their passion for science fiction lives on in these pages.

Analytical Laboratory and My Ratings

You may or may not recall the fact that, for some reason, Campbell never published the AnLab results for the June 1942 issue of Astounding. Well, despite being nearly half a year late, we get the AnLab for both June and September 1942 in this issue. My ratings for those issues appear in parentheses.

AnLab Results for June 1942

- Bridle and Saddle by Isaac Asimov 1.55 (1)

- Proof by Hal Clement 3.40 (2)

- Heritage by Robert Abernathy 3.7 (10)

- On Pain of Death by Robert Williams 3.8 (3)

- My Name Is Legion by Lester del Rey 4.0 (4)

AnLab Results for September 1942

- Nerves by Lester del Rey 1.00 (3)

- The Barrier by Anthony Boucher 1.81 (4)

- The Twonky by Lewis Padgett 3.5 (5)

- With Flaming Swords by Cleve Cartmill 3.8 (7)

- Pride by Malcolm Jameson 3.9 (1)

And here are my ratings for the current issue:

- Four Little Ships by Murray Leinster

- Sand by Colin Keith

- Minus Sign by Will Stewart

- The Gentle Pirates by John Berryman

- Overthrow by Cleve Cartmill

- Not Only Dead Men by A. E. van Vogt

Possibly, this is the first time that van Vogt has taken last place in my rankings.

In Times To Come

Once again, Campbell bemoans that fact that many of his reliable authors are involved in the war effort with little time to write. He then goes on to talk about three new writers of “major promise” that have been developed, a statement that is a white lie. He names Padgett, Will Stewart, and Hal Clement as the three writers. Of course, Padgett is not new, it's simply C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner in disguise. And Will Stewart, of course, is Jack Williamson. Hal Clement is legitimate in this case.

The rest of the In Times To Come section doesn't mention any stories. Instead, Campbell talks about how he is running an “unofficial recruiting office” for the war effort,

I know a place where some young engineers, with engineering degrees and a little experience, a degree at least, are badly needed. The work being done is most naturally, decidedly, secret…. It's a a chance to really serve your country in a way that will make your training… count for maximum results.

I thought, perhaps, he was referring to the Philadephia Navy Yard, where Heinlein, Asimov, and de Camp were, or would be working. But he doesn't say. Instead, he encourages readers to write in if they are interested, and he will see to it that their letters reach official channels.

So, no coming attractions from Campbell. Fortunately, I happen to have the December 1942 Astounding right here next to me. The lead novelette is A. E. van Vogt's “The Weapon Shop.” Also stories by Cleve Cartmill, Lewis Padgett, Ross Rocklynn, Frank Belknap Long, an multipart article by de Camp, and another Probability Zero column.