The road to retirement is rocky, it is guarded by bridge trolls and beset by obstacles. There are pits of despair. There are staggering peaks and terrifying wonders. There is so much ground to cover.

-Overheard in a physician's lounge somewhere in Kansas.

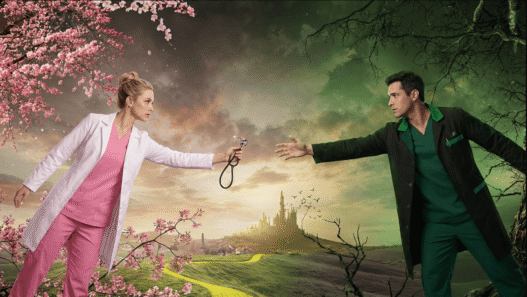

“Somewhere Over the Rainbow”

I see you there, my fellow traveler. You're exhausted, aren't you?

You've been walking this yellow brick road for what feels like forever—through the dark forests of medical school, across the treacherous mountains of residency, past the poppy fields of fellowship. Your feet ache from weekend call. Your back hurts from hunching over electronic medical records. You're tired in ways that sleep can't fix.

Come, sit with me here by the side of the road. Rest a moment. Let's talk about what lies ahead, because the journey you've been on is about to change.

You see that shimmering city on the horizon? That emerald glow that's kept you walking all these years? That's your retirement—your promised land.

That magical place where pagers don't exist, where EMRs can't find you, where you're no longer held hostage by RVU targets and patient satisfaction scores.

You obsess over the numbers, I know.

Will we have enough? When can we leave? How much do we need in our accounts before we can finally click our ruby slippers three times and escape this road?

$3 million? $4 million? $5 million? When will it be enough to leave this road behind?

But here's what I need to tell you, friend—the truth most retirement planners won't share: the path ahead is more treacherous than you realize. You'll traverse poppy fields of lifestyle inflation that steal your savings while you sleep, face market storms that devastate portfolios overnight, encounter advisors pushing expensive products with hidden fees, and confront the most seductive trap of all—the belief that working “just two more years” is safer than retiring while your health permits.

And perhaps the most unsettling truth is that the Emerald City you've been pursuing for 30 years often looks far different upon arrival than you imagined.

The journey to physician retirement is more than just about reaching a destination, it's about surviving and thriving through the road itself.

And here's the wicked twist that nobody tells you: while you need to pace yourself like a marathon runner during your saving years, you must sprint like your life depends on it during your early retirement years.

Because it does. The average age when health significantly declines is 63.9 years. Not 75. Not 80. Sixty-three point nine.

I'm a hospice physician, and I need to tell you something that haunts me: Every so often, I have the profound sadness of caring for fellow physicians as they approach the end.

Some of these colleagues worked into their early 70s, always planning to retire “next year,” always chasing one more milestone, one more financial goal. They deferred their dreams of travel, of time with grandchildren, of finally pursuing passions beyond medicine.

And now here they are, with all the wealth they accumulated, facing that final river crossing. You know the one — the River Styx, where Charon ferries souls to the other side.

When we cross that river, we take nothing with us. Not the portfolio balance. Not the extra years of work. Not the “security” of one more year's salary. On those days, I hate my job.

So yes, rest here with me. Catch your breath. Because we need to talk about the real journey ahead—not the one your financial advisor showed you on their Monte Carlo simulation, not the one your senior partners told you about, but the actual, messy, complex, beautiful, terrifying journey from where you are now to where you want to be.

And more importantly, we need to talk about how to make sure you arrive at that Emerald City while you're still healthy enough to enjoy it.

“Are People Born Wicked? Or Do They Have Wickedness Thrust Upon Them?”

This profound question from Glinda in Wicked applies perfectly to physician retirement planning mistakes.

Are physicians naturally bad at retirement planning, or does our medical training system, delayed earning potential, student loan burden, and culture of delayed gratification conspire to create these failures?

According to financial professionals, nearly half believe the most wicked mistake in retirement planning is underestimating inflation's impact on savings.

Fortysix per cent cite underestimating life spans as the second most dangerous miscalculation.

For physicians, these challenges compound uniquely: starting careers around age 30, we carry six-figure student debt, facing lifestyle inflation as income finally arrives, and experiencing career burnout that may force earlier-than-planned retirement.

This fundamental disconnect between present and future self is the original sin of physician retirement planning.

We save for a theoretical person we've never met, in a future we cannot accurately imagine, using assumptions that are often wildly optimistic—all while working 50-60 hour weeks that leave little time for financial planning.

“Pay No Attention to That Man Behind the Curtain”

The retirement industry itself operates much like the Wizard of Oz—lots of smoke, mirrors, and impressive displays designed to obscure the fact that behind the curtain, there's often just guesswork and generic advice dressed up as personalized wisdom.

Just as Dorothy needed to pull back the curtain to see the truth, you must be vigilant in selecting who guides your retirement journey.

Don't be fooled by impressive credentials, slick presentations, or promises that sound too good to be true. Like the Wizard who had “no power” but needed Dorothy's compliance, many advisors push one-size-fits-all solutions because they're easier to sell than personalized strategies.

But here's the important truth: good financial advisors do exist — true fiduciaries who put your interests first, who understand physician-specific challenges, who customize strategies for your situation rather than forcing you into their predetermined mold.

You just have to be selective enough to find them. Look for fee-only advisors who specialize in working with physicians, who understand the nuances of student loans, practice transitions, and the unique tax situations physicians face.

Ask hard questions. Verify their credentials. Check their disciplinary history. Don't settle for generic advice when your situation demands expertise.

Consider the standard 4% rule, that magical incantation promising you can withdraw 4% of your portfolio annually and never run out of money. But here's what most advisors won't tell you: that “4%” was originally 4.15%, rounded down by mainstream media because it was easier to remember. Bill Bengen, who created the rule, has since updated his analysis with additional asset classes—it's now actually 4.8%. And the rule is overly conservative because it assumes ALL your spending adjusts with inflation every year. Your mortgage doesn't inflate. Your property taxes may barely budge. Yet the 4% rule treats every dollar as if it needs an annual inflation adjustment.

For physicians retiring in their late 50s or early 60s, the traditional approach gets even more problematic. Yes, you'll need a slightly lower withdrawal rate for a 40-year retirement versus the standard 30-year horizon—but only about 0.6% lower. So instead of 4.8%, you'd use roughly 4.2%. But here's where physician flexibility becomes powerful: unlike traditional retirees in their 70s who have settled into fixed spending patterns, limited ability to work, and high essential expenses, physicians retiring early typically have significant discretionary spending (travel, dining, hobbies), the ability to pick up locum work if needed, and the flexibility to adjust their lifestyle.

A good advisor who understands this will introduce you to a discretionary spending strategy: Calculate what percentage of your budget is truly discretionary versus essential. If 50% of your spending is discretionary, research shows you can safely withdraw 5.5% initially (not 4%) with a 98.28% probability of success over 40 years—IF you follow simple rules during market downturns. When the market drops more than 20% from its highs, you cut discretionary spending to zero. When it's down 10-20%, you cut discretionary spending by half. Otherwise, you spend your full budget. Your essential expenses (housing, healthcare, food) continue adjusting with inflation, but your discretionary spending remains flat—which actually aligns with research showing retirement spending naturally decreases over time anyway.

This means a physician with $2 million who wants to spend $80,000 annually could retire using a 4% withdrawal rate, or they could retire with just $1.45 million using a 5.5% rate (with 50% discretionary spending)—retiring years earlier while maintaining nearly identical success probabilities. The tradeoff? In bear markets, you're hiking local trails instead of touring Patagonia. You're cooking at home instead of dining out three times weekly. But your house is paid for, your healthcare is covered, and you're living this life at 58 instead of 65.

As Elphaba discovered when she finally met the Wizard, “You have no real power!” To which the Wizard replied, “Exactly. That's why I need you.”

Don't give your power away to someone who doesn't deserve it. Find an advisor who empowers you with knowledge and personalized guidance, not one who needs your compliance to maintain their illusion of expertise.

“I'm Melting! Melting!”

The scariest moment in physician retirement isn't when you retire—it's when you realize your money is melting away faster than you anticipated. For physicians who often accumulate the bulk of their wealth in their final 10-15 earning years, the sequence of returns risk is particularly brutal.

Imagine two physician couples, both retiring with $4 million portfolios, both withdrawing $160,000 annually. Dr. A retires into a bull market and enjoys strong returns for the first five years. Dr. B retires into a bear market and suffers losses in the early years. Even if they experience identical average returns over 30 years, Dr. B's portfolio may be completely depleted while Dr. A still has substantial assets.

The first five to ten years of physician retirement are crucial. This is your vulnerable period, when portfolio losses combined with withdrawals can create irreversible damage. The solution isn't complex: maintain a substantial cash buffer (4-5 years of expenses for physicians with longer retirement horizons) to prevent forced selling during downturns, and remain flexible with discretionary spending. The cruise through Europe can wait a year if markets tank. Being willing to cut back 20% during difficult market conditions dramatically improves portfolio longevity.

But here's the critical warning: don't jump off the broom when turbulence hits. The worst retirement mistake is panicking during a bear market and selling stocks at the bottom to fund your lifestyle. When your portfolio drops 30% and financial news is screaming apocalypse, stay on the broom. Use that cash buffer you built. Cut discretionary spending. Pick up some locum work if needed. The market will recover—it always has—but only if you stay invested and avoid locking in losses by selling low.

Many physicians maintain part-time clinical work in early retirement not just for income, but for identity and purpose. This allows you to spend more freely on experiences while maintaining cash flow, reducing portfolio withdrawal stress during these vulnerable years. For example, I do 1 to 2 days per week of clinical work with a hospice company via telemedicine. It checks off several boxes -I feel like I am making an impact and I make a great income.

“Defying Gravity”

One of Wicked's most powerful songs is “Defying Gravity,” where Elphaba sings: “Something has changed within me. Something is not the same. I'm through with playing by the rules of someone else's game. Too late for second-guessing. Too late to go back to sleep. It's time to trust my instincts, close my eyes and leap.”

This is the crucial mindset shift for physician retirement planning: you must defy the conventional wisdom gravity that keeps you grounded in traditional thinking.

Defy delayed gratification in retirement: You've already delayed gratification through medical school, residency, fellowship, building a practice. Continuing to delay in retirement is a strategic error. While your colleagues in business started earning and enjoying life in their 20s, you were taking Step exams and surviving Q4 calls. Don't compound that by deferring enjoyment for another decade in retirement. Health declines around age 64. Your window for vigorous adventure is NOW, not later.

Here's a truth that should terrify every physician planning to work “just a few more years”: On average, we get 80 summers in a lifetime—if we're lucky. By the time you finish fellowship at 35, you've already used up 35 of them. Work until 65? You've spent 65 summers, leaving just 15 remaining—and remember, health significantly declines at 63.9 years. Those final summers won't include hiking Patagonia or cycling through Vietnam. They'll include physical therapy appointments and medication adjustments.

The problem is, you think you have time. You don't. Stop waiting for the “right time” to book that trip, to spend evenings with your children instead of finishing notes, to watch the sunrise instead of pre-rounding. The physician who works until 68 to accumulate $5 million has already missed 68 summers. The one who retires at 58 with $3 million has 22 summers remaining—and crucially, they have their health to enjoy them. Don't put off the trip. Don't defer telling people you love them. Don't wait for life to begin after you hit some arbitrary financial milestone.

Defy lifestyle inflation during your earning years: The physician income jump from residency to attending is intoxicating, but lifestyle inflation is insidious. The physician earning $350,000 who lives like they earn $250,000 can retire comfortably in their 50s. The one who spends everything will work well into their 60s—often past the point when their health would allow them to fully enjoy retirement.

Defy the culture of working until you drop: Medicine has a macho culture around working into your 70s, never retiring, dying with your stethoscope on. This is gravity masquerading as virtue. If you've planned properly, retire when you're healthy enough to enjoy it—not when your body forces you. The physician who retires at 60 with $4 million and good health is wealthier than the one who works until 68, has $5 million, and can barely walk.

“Follow the Yellow Brick Road”

So what's the right path for physicians? Here's the uncomfortable truth: there isn't one yellow brick road. There are infinite paths, and yours will be unique to your specialty, practice setting(private vs academic, ambulatory vs hospital-based), family situation, health, and priorities. However, five principles apply to nearly every successful physician retirement journey.

First, attack student loans strategically and start saving during residency—yes, residency. Even if it's just $200-500 monthly, the habit matters more than the amount. Residents who save anything have dramatically higher net worth trajectories than those who wait until attending life. Whether you pursue PSLF through hospital employment or aggressively pay off loans in private practice, have a clear strategy by age 35. As an attending, build your savings infrastructure: max out 401(k)/403(b) ($24,500 in 2026, or $32,500 if over 50), backdoor Roth IRA ($7,500), HSA if eligible ($4,400 individual, $8,750 family). Work toward saving 20-25% of gross income.

Second, invest appropriately for the longevity you'll likely experience. With a potential 35-40 year retirement horizon, physicians need significant equity exposure even in retirement. A 60-year-old physician retiring with a 60/40 portfolio may find themselves outliving their money if they experience below-average returns. Consider 70/30 or even 80/20 in early retirement, gradually shifting more conservative only in your mid-70s. Target-date funds often shift too conservative too early for physician retirees. And for high-earning physicians, Social Security represents a smaller percentage of retirement income than other professions—but it's still meaningful guaranteed inflation-adjusted income. For a physician couple with other retirement resources, delaying Social Security until 70 can add hundreds of thousands of dollars over their lifetimes.

Third, plan for the physician-specific costs and transitions that generic retirement advice ignores. Purchase own-occupation disability insurance in residency or early attending years when you're young and healthy—young physicians are far more likely to become disabled than to die prematurely. Address long-term care insurance in your 50s before premiums become prohibitive. Budget for malpractice tail coverage ($20,000-100,000 depending on specialty). Decide strategically about maintaining your medical license, DEA registration, and board certification in retirement—don't let them lapse by default. And don't count on practice sale proceeds; factor them at zero when planning retirement, and anything you actually receive becomes a bonus.

Fourth, build identity beyond medicine years before retirement. Your medical license isn't your identity. Start cultivating interests, relationships, and pursuits outside of medicine now. The physician whose entire sense of self comes from their white coat will experience retirement as existential crisis. The physician who's already developed as a person beyond their profession enters retirement as liberation. Take up serious hobbies, volunteer in non-medical capacities, cultivate friendships with non-physicians, develop skills unrelated to medicine. This isn't optional—it's essential. The physicians who thrive in retirement are those who cultivated identity beyond medicine years before their last patient encounter.

Fifth, and most critically: plan the sprint, not just the marathon. While SAVING for retirement requires marathon discipline, LIVING in retirement should be a sprint in your early years. Don't meticulously plan your finances for age 85 while ignoring that your best years are 60-70. If your retirement plan requires you to withdraw 3-4% annually forever, consider withdrawing 5-6% in your first decade while you can fully enjoy it, then adjusting downward. Research shows retirees naturally spend less as they age—not by choice, but by necessity as energy and mobility decline. One physician retiree noted: “We hiked Patagonia at 62. By 68, just climbing stairs in Europe was challenging.”

“There's No Place Like Home”

After all the adventures, battles, and revelations, Dorothy's greatest insight was that what she was seeking was with her all along. The Emerald City wasn't the answer—home was. The journey revealed this truth.

Similarly, successful physician retirement isn't really about reaching some magic number in your 401(k) or 457(b). It's about the journey of building a life that's sustainable, meaningful, and aligned with your actual values rather than the borrowed expectations of medical culture. The physician community often creates artificial benchmarks: “You need $5 million to retire,” “Real doctors work until 70,” “You can't retire until your kids are through college AND medical school.” Research consistently shows that beyond a certain threshold (generally around $75,000-100,000 in annual household income, adjusted for location), additional money provides diminishing returns on life satisfaction.

Just as Dorothy collected her enduring friends along the yellow brick road—the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion—your pre-retirement years show you which relationships are genuine and which are circumstantial. Retirement will strip away hospital colleagues, referral relationships, and professional networks, leaving only what's authentic. The physician who cultivates friendships outside of medicine during their working years enters retirement with a social safety net.

As Fiyero noted in Wicked (with delicious irony), “I happen to be genuinely self-absorbed and deeply shallow.” His self-awareness, even in jest, points to an important truth: understanding yourself—your actual needs, values, and tendencies—is more important than following some generic physician retirement formula promoted at medical conferences. The physician who retires with $4 million but no identity beyond medicine is impoverished. The physician who retires with $2.5 million but deep relationships, meaningful pursuits, and strong sense of self is wealthy.

“We're Off to See the Wizard”

Here's the final, most important truth about physician retirement planning: you're already on the journey. The yellow brick road isn't something you step onto at some future date—you're walking it right now, with every financial decision you make, every relationship you nurture, every skill you develop beyond medicine.

The Emerald City shimmers on the horizon, but it's not really the point. The point is who you become on the journey, what you learn about yourself beyond your white coat, and whether you're building a life that's sustainable and meaningful rather than just lucrative and impressive.

But here's what Dorothy learned, what Elphaba discovered, and what every successful physician retiree eventually realizes: you had the power all along. Not to magically transport yourself to some perfect retirement destination with a click of your heels, but to take control of your financial life, to make intentional choices aligned with your values rather than medical culture's expectations, to adapt when circumstances change, and to find meaning and purpose beyond the practice of medicine.

As Glinda posed at the beginning: “Are people born wicked? Or do they have wickedness thrust upon them?” The same question applies to physician retirement readiness. The answer doesn't really matter. What matters is recognizing that you have agency. You can educate yourself about finances. You can start saving aggressively the moment you become an attending. You can resist lifestyle inflation. You can build relationships and interests outside of medicine that will sustain you when your clinical career ends.

The journey to physician retirement isn't about reaching perfection—it's about making consistent progress toward a sustainable future while also living meaningfully in the present. It's about finding your own yellow brick road and having the courage to follow it, even when the path differs from what your colleagues are doing, even when the destination is uncertain.

Don't wait until your body forces the decision. Don't defer until “later” what your health permits today. The Go-Go years don't wait. They don't care that you want to work “just two more years.” They don't care that your portfolio would be larger if you waited. They simply pass, indifferent to your plans.

As one physician who retired at 59 after accumulating $3.5 million noted: “I finally understood that working until 65 to have $4.5 million meant sacrificing my healthiest years for money I'd likely never use. My partners thought I was crazy. Five years later, I've hiked Patagonia, cycled through Vietnam, spent months with grandchildren, and pursued photography seriously. My partners are still working—and complaining about it. I have enough. They have more. I'm wealthier.”

Follow your yellow brick road. Defy gravity. And remember—when you cross the River Styx, you take nothing with you. Not the portfolio balance. Not the extra years of work. Not the security of one more year's salary. But you will carry the memories of the life you lived, the adventures you had, the people you loved, and the dreams you pursued while your health permitted.

You had the power all along.